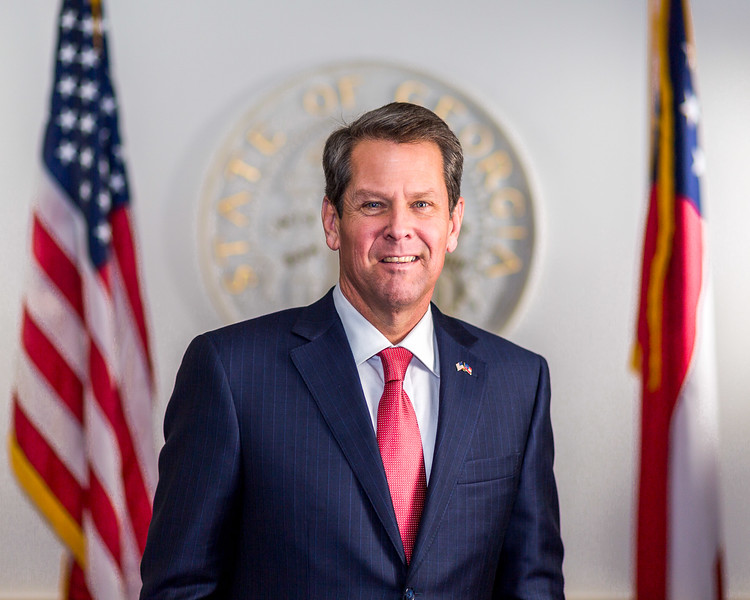

ATLANTA – Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger pushed back Tuesday against criticism of the elections overhaul the Republican-controlled General Assembly passed last week.

Democrats including President Joe Biden and voting rights advocacy groups have slammed the legislation as part of a bid by GOP state lawmakers across the country at voter suppression following Republican defeats in last year’s elections.

The bill imposes new ID requirements on absentee voting, limits the placement of drop boxes for absentee ballots to inside election offices and early voting locations, and gives state election officials the authority to take over poor-performing local election boards.

But Kemp noted Tuesday the bill also expands early voting to two Saturdays and gives counties the option to hold poll hours on two Sundays. An earlier version of the legislation had proposed shrinking early voting on Sundays.

“How is this suppression when you’re adding opportunities for more weekend voting?” the governor asked.

Kemp also pointed out that the bill codifies drop boxes for absentee ballots for the first time in Georgia. Drop boxes were allowed during the last election cycle as part of the public health emergency he declared because of the coronavirus pandemic.

“The other side is trying to act like something was going to be taken away,” he said. “If we hadn’t addressed [the drop boxes] in this bill, they would have gone away.”

Kemp said the bill does away with the signature match method for processing absentee ballots in favor of a voter ID requirement to ease the burden on local elections officials.

The huge surge of absentee voting in the 2020 election cycle due to the virus was cumbersome on local elections officials forced to match signatures, he said.

“[Going to voter ID] is going to help elections officials speed up the process,” he said.

The governor defended a controversial ban on non-poll workers handing out food and drinks within 150 feet of voters waiting in line outside polling places as a way to prevent illegal electioneering.

“We’ve had rules about electioneering within 150 feet of the polls for a long time,” he said. “The real question ought to be why are they standing in line so long? … People ought to be able to vote in 30 minutes to an hour.”

Raffensperger said the new law will still let groups give “nonpartisan, bipartisan water without campaign stickers” to poll workers who will distribute it.

But the secretary of state stopped short of giving the bill a full endorsement, noting other contentious measures that strip him of voting powers on the State Election Board. Instead, the new law calls for the board to be chaired by an official appointed by either the General Assembly or the governor.

“When you have direct accountability and you have an elected official at the top, then the voters can hold that person accountable,” Raffensperger said. “What you really are creating is a little mini-Washington, D.C., a non-accountable board … [where] no one gets anything done. … I think at some point they’ll regret this decision.”

Meanwhile, Kemp’s signing of the election bill has drawn a trio of lawsuits aimed at blocking the voting measures from taking effect on grounds they suppress voter access, particularly in Black and low-income communities.

Attorneys representing a host of suing groups including the NAACP, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the New Georgia Project argue the election changes violate the federal Voting Rights Act and constitutional free-speech rights.

“It’s essentially a storm that the legislature and the governor have unnecessarily created that they’re leaving for others to address,” said Nancy Abudu, the SPLC’s deputy legal director for voting rights. “Our lawsuit is taking this issue directly to the courts in an effort to block this behavior, this suppressive attempt.”

The suing groups dismiss arguments that the law expands voter access by adding more weekend early-voting hours and officially legalizing drop boxes by pointing to the totality of the law.

“Each of these provisions taken together demonstrate very clearly that this law is aimed at suppressing the vote, not expanding it,” said Sophia Lin Lakin, deputy director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. “Picking apart each individual provision … is simply ignoring the fulsome thrust of the really terrible impact of this law.”

Kemp accused the law’s opponents of pushing a narrative aimed at benefiting Democrats politically. He cited as an example Biden’s portrayal of the law as a “Jim Crow in the 21st century” blow at voting rights won during the long civil rights struggle in America.

“We know their playbook,” Kemp said. “They target certain sections of the bill. Then, when it changes, they target something else.”