ATLANTA – As overdoses have skyrocketed in Georgia – more than 13,000 this year alone, according to the state Department of Public Health — so has demand for the life-saving drug naloxone, which reverses the deadly effects of an opioid overdose.

People who use drugs – or those who are frequently around them – are encouraged to keep naloxone on hand. It comes in several different forms, including as a liquid that can be injected and a nasal spray. The drug can almost instantly bring someone back from an overdose but will not harm a person if they have not overdosed.

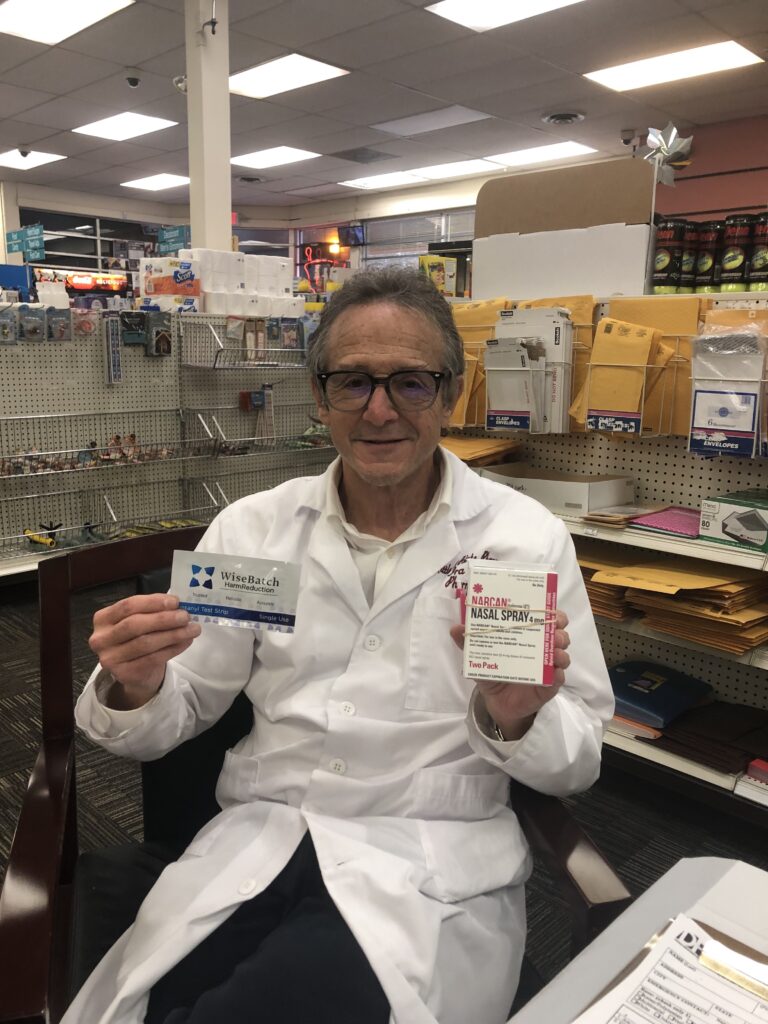

But the miracle drug isn’t cheap. A two-unit box of Narcan, the nasal spray version of the drug, costs at least $45. That puts a strain on local governments, nonprofit organizations, and drug users who want to make sure the lifesaving drug is easily accessible.

The drug can be even more costly for consumers who want to purchase it at a pharmacy. It ranges between $40 and $143 at Atlanta-area pharmacies for a box of two units of the nasal spray, according to drug-pricing website GoodRx.

The cost is further compounded by the influx of the potent opioid fentanyl, which is now found mixed in many types of illicit drugs. Fentanyl-fueled overdoses require more naloxone to treat than past non-fentanyl overdoses, observers from across the state noted.

Whereas in the past, two units of Narcan may have been enough to keep someone alive until emergency services arrived, now one overdose may require four, five, or even six units, said Ira Katz, an Atlanta pharmacist.

Katz has sought to circumvent the high costs of naloxone by forming a partnership with the Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition. His Little Five Points Pharmacy, located in the heart of an artsy and alternative neighborhood that draws visitors from across the state, hands out the drug for free.

“We want to do what we can to try to make it affordable,” said Katz, who has personally reversed overdoses at least seven times. He said the pharmacy gives out about 10 to 12 boxes of the drug per day, and he has people drive in from all over Georgia to get it.

Sometimes, pharmacists can give out free samples of the drug to those in need, said Jonathan Marquess, a vice president of the Georgia Pharmacy Association.

“We should never have anyone walk in a pharmacy and not be able to get a Narcan prescription,” Marquess said, either because the pharmacy does not have the drug in stock or because of cost.

“The numbers have gone up dramatically in the last few years,” said Robin Elliott, a co-founder of Georgia Overdose Prevention, a group that mails free naloxone kits out across the state.

Last month alone, the group distributed almost 2,600 kits. It sent out 28,000 in a 12-month period. Because it has a limited supply, the group tries to target those who are at highest risk and who are uninsured, Elliott said.

Other community groups across the state also distribute naloxone for free. Access Point of Georgia, a nonprofit group that serves Athens-Clarke, Oglethorpe, Madison, and Jackson counties, has had 337 overdose reversals reported so far this year, said Riley Kirkpatrick, the group’s founder. That number is likely an undercount, Kirkpatrick said, since not all overdose reversals are reported to the group.

Many law enforcement officers and first responders carry the drug with them. For example, Jackson County’s emergency services has attempted 172 reversals so far this year, said Tim Grice, assistant director of Jackson County Emergency Medical Services.

“[Cost] is always on our mind,” Grice said, though the county has had sufficient supply so far.

Local groups and governments should begin to see some additional financial support for distributing naloxone due to the influx of funds from the state’s opioid lawsuit settlements. Last year, the state announced it would be receiving almost $17 million from a settlement with global consulting firm McKinsey for that company’s role in promoting the drugs.

Georgia will use around $2 million from the settlement to supplement emergency service providers with the drug starting this month, said Eric Jens of the state Department of Public Health.

The department has also launched an Overdose Response Kit pilot project in locations where overdoses may occur, including restaurants, bars, and hotels. The project will install kits that include instructions about how to use naloxone, said Jens.

Money from the McKinsey settlement and other sources funds the purchase of more than 70,000 units of the drug for distribution via community groups and events, the Georgia Overdose Prevention Project, and local public health departments, said David Sofferin of the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities.

Another $1 million from the McKinsey settlement has been allocated to the Georgia Harm Reduction Coalition to help distribute naloxone in communities across the state, he said. The agency trains law enforcement officers and first responders on how to use the drug.

The influx of the McKinsey settlement money comes on the heels of steps the state has already taken to address the overdose crisis.

A 2014 law provides legal amnesty to anyone who calls 9-1-1 after an overdose, shielding someone trying to get help for a friend or family member who has overdosed from legal prosecution for drug use. In 2017, Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, then-commissioner of the Department of Public Health, issued an order that essentially gave all Georgians a standing prescription for naloxone, obviating the need to see a doctor.

During the last legislative session, the General Assembly approved legislation that removed fentanyl test strips from the list of illegal drug paraphernalia. The test strips help users determine whether their drugs have been mixed with potentially deadly fentanyl.

At the federal level, the Food and Drug Administration is moving to fast-track an application from Narcan’s manufacturer to make the drug available over the counter as soon as next year. That could help bring down the drug’s price as competition increases, said Mary Sylla, director of overdose prevention and policy for the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

It’s essential to make sure the drug is available everywhere, including schools, sporting venues, restaurants, government buildings, and places of worship, said Jeff Breedlove, chief of communications and policy at the Georgia Council for Recovery. He would like to see naloxone become as common as the defibrillator kits widely available in public places today, and he praised Delta Air Lines’ decision to ensure each plane has naloxone available on board.

“Government, business, and faith leaders have to accept the reality that overdose deaths are at historic highs, that their constituents and customers are dying and families need their help to save lives,” Breedlove said. “Forty-five dollars [the cost of naloxone] is a lot less money than the cost of a casket.”

This story is available through a news partnership with Capitol Beat News Service, a project of the Georgia Press Educational Foundation.