Georgia’s new voting machines will face their first major test in a June 9 primary election that has created far different logistical challenges for state officials than were anticipated before the coronavirus pandemic struck.

The new machines, purchased last summer for $104 million, were already under intense scrutiny as Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger’s office pushed to have the 30,000 new devices rolled out by the March 24 presidential preference primary, all while legal challenges sought to have them blocked.

Then coronavirus hit, upending the game plan for the March 24 contest in which the voting machines were poised for their first statewide use. Since then, primary elections have been postponed twice to June 9, precincts in high-volume voting areas like Atlanta have shuttered over safety concerns and Raffensperger has pushed for Georgians to hand in absentee ballots rather than head to the polls.

“What voters have to understand is that it’s going to look a little bit different when they show up this time,” Raffensperger said at a recent news conference.

“The fewer people voting on the actual election day,” he added, “the safer it will be for the voters, poll workers and all Georgians.”

Purchased last July from Dominion Voting Systems, the new machines – called ballot-marking devices – involve touchscreens and scanners that record a paper print-out of a voter’s completed ballot. State officials hail the new machines as more secure than the old all-electronic machines, which have been scrapped over cybersecurity concerns after 18 years of use.

Critics of the new machines have continued pushing for Georgia to adopt an all-paper voting system, arguing the new devices still record votes electronically and do not provide enough of an audit trail. Lawsuits filed in federal court against Raffensperger’s office aim to halt the new machines in Georgia, though judges overseeing those cases so far have not issued any injunction orders to do so.

To date, Raffensperger said the new machines have not experienced any major technical issues since being installed in time for the March 24 presidential primary. They have been used by hundreds of thousands of Georgians in early voting this year and during a six-county test run last fall, in which county officials reported some minor glitches.

“They’ve worked amazing,” Raffensperger said, while acknowledging that “we haven’t gotten the full use of those [machines] that we would like because of COVID-19.”

Coronavirus, which had sickened more than 45,000 people and killed 1,974 in Georgia as of Friday afternoon, has prompted elections officials to shift attention from having the new machines go off without a hitch to making sure polling places are kept clean and both voters and poll workers have protective supplies to stay safe.

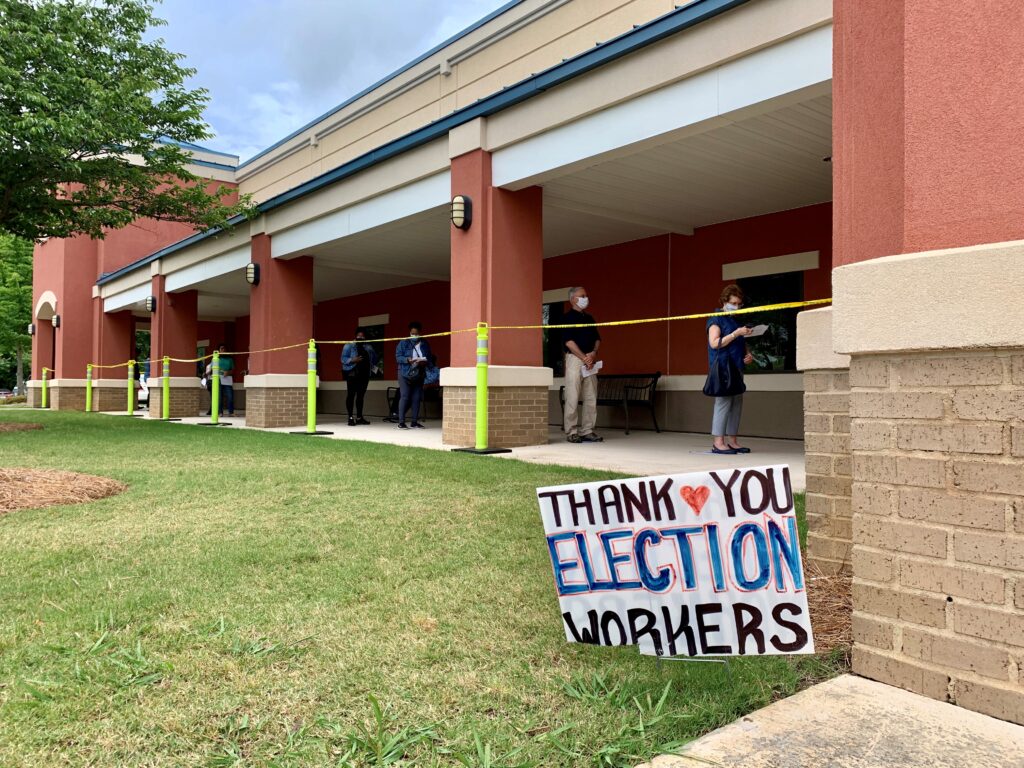

To curb risks of spreading the virus, voters are being spaced out six feet apart from each other in line at local precincts and poll workers will all wear masks and gloves, Raffensperger said. His office is also supplying counties with roughly 60,000 stylus pens for voters to use on the touchscreens rather than their fingers. Without the styluses, polling places would have to completely shut down the touchscreens to disinfect them after each use.

On top of distancing and sanitizing measures, officials expect voting to take longer than normal due to fewer precincts being open in areas like Atlanta, as some local churches and schools that usually serve as precincts back out over coronavirus concerns.

In Savannah, the Chatham County Board of Elections is pushing to open alternative polling places after 12 of the county’s 92 voting sites “were uncertain.” And Fulton County, the state’s most populous, has lost more than 30 voting sites in recent weeks from its nearly 200-site total and is “struggling with Election Day locations,” said the county’s election director, Rick Barron.

“This has been an unprecedented situation for not only Fulton County but also other counties around the state,” Barron said at a recent news conference.

To ease the pressure of in-person voting, state and county elections officials have spent weeks urging Georgians to cast ballots by mail after Raffensperger’s office sent absentee ballot applications to all of the state’s nearly 7 million registered voters starting in March. So far, roughly 600,000 people have sent in absentee ballots of the more than 1.5 million who requested them, according to Raffensperger.

Handling the avalanche of absentee ballot requests has been challenging for many county elections officials, including Barron. Like other counties, his Fulton County staff have been swamped with processing absentee ballot applications and returned ballots, with many voters still complaining they have not received mail-in ballots weeks after requesting them.

Officials have asked voters to be patient as they sift through absentee ballot requests submitted by mail and online in recent weeks.

“It’s almost as though we’ve added a different type of an election on top of the one that we’re already running,” Barron said. “It has split our resources.”

Meanwhile, time is running out for mail-in voting. Ballots must be cast or received by county offices no later than 7 p.m. on June 9 or they will not count, Raffensperger said. If voters wait until the final few days, their absentee ballots may not circulate quickly enough through the mail to make it.

“It does put you at the mercy of the United States Postal Service,” Raffensperger said.

That time crunch prompted one member of the Georgia House Democratic Caucus, Rep. Donna McCleod, to conclude voters should ditch the mail-in method if they have not received an absentee ballot by Friday, May 29. If that’s the case, voters can still fall back on the new machines to cast their ballot.

“Please, please, please stay safe,” said McCleod, D-Lawrenceville. “This is not worth your life, but it is important for us to participate in our democracy.”