A potential vaccine for COVID-19 being tested at Emory University in Atlanta has shown promising early results after months of clinical trials, researchers announced late Tuesday.

The candidate vaccine appears to be producing high levels of virus-blocking antibodies and interacting well with immune systems in 45 adult test subjects who volunteered for the project, said Dr. Nadine Rouphael, an associate professor of medicine at Emory’s School of Medicine and interim director of the Hope Clinic at Emory’s Vaccine Center, who is helping lead the vaccine study.

In a news conference Tuesday, Rouphael said she feels optimistic about the early trial results but that “time will tell” whether the vaccine may be deemed effective and safe enough for mass production.

“Having a vaccine candidate that works and is safe is really the most important part,” Rouphael said.

No serious negative reactions have been seen so far, though more than half of the test subjects reported experiencing fatigue, headaches, chills and pain at the injection point, Rouphael said.

Test subjects ages 18 to 55 were given two doses of the candidate vaccine. Minor adverse reactions were seen most often in the second dose and at higher dosage amounts.

Results of the trial’s first phase were published Tuesday in the New England Journal of Medicine. Emory is one of two sites in the U.S. where the candidate vaccine has undergone trial runs since March.

Rouphael and a team of researchers led by the Seattle-based Kaiser Permanent Washington Health Research Institute now plan to conduct trials on hundreds more volunteers in Atlanta and across the country.

She urged people interested in volunteering for the trial’s next testing phase to sign up at https://www.coronaviruspreventionnetwork.org/.

Rouphael also emphasized researchers need volunteers from populations hit hardest by the coronavirus including Black and Latino communities and elderly persons.

“It’s really important to make sure that all of us in the community sign up,” she said.

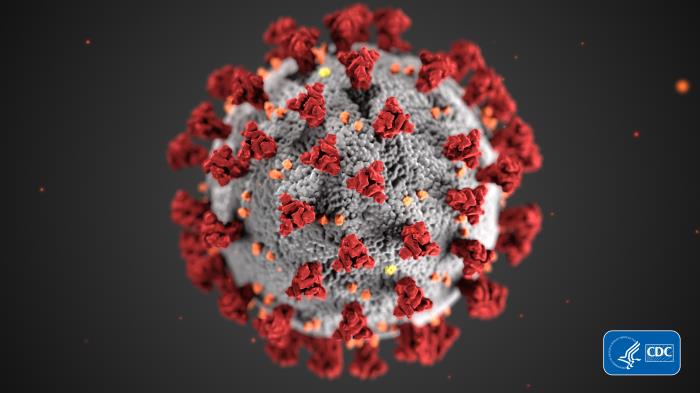

Unlike traditional vaccines that introduce disease-causing organisms, the vaccine being tested at Emory involves using genetic sequencing to create proteins that mimic the novel strain of coronavirus and trigger a response from the patient’s immune system to erect safeguards.

These so-called mRNA vaccines can be cheaper and faster to produce but are less tried-and-true than traditional vaccines, according to the nonprofit PHG Foundation at the University of Cambridge.

The potential coronavirus vaccine, called mRNA-1273, was developed in roughly two months by the Massachusetts-based company Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which kicked off clinical trials in Seattle in March.