ATLANTA – Rural Georgians from business owners to teachers to elected officials know one of the region’s biggest challenges is inadequate internet connectivity, particularly amid a pandemic that is forcing people to stay home.

But the lack of population density in rural areas and high rates of poverty are combining to make extending high-speed broadband service into rural communities a daunting task.

The General Assembly passed legislation in June aiming to use Georgia’s 41 electric membership corporations (EMCs) as the vehicle for addressing the problem.

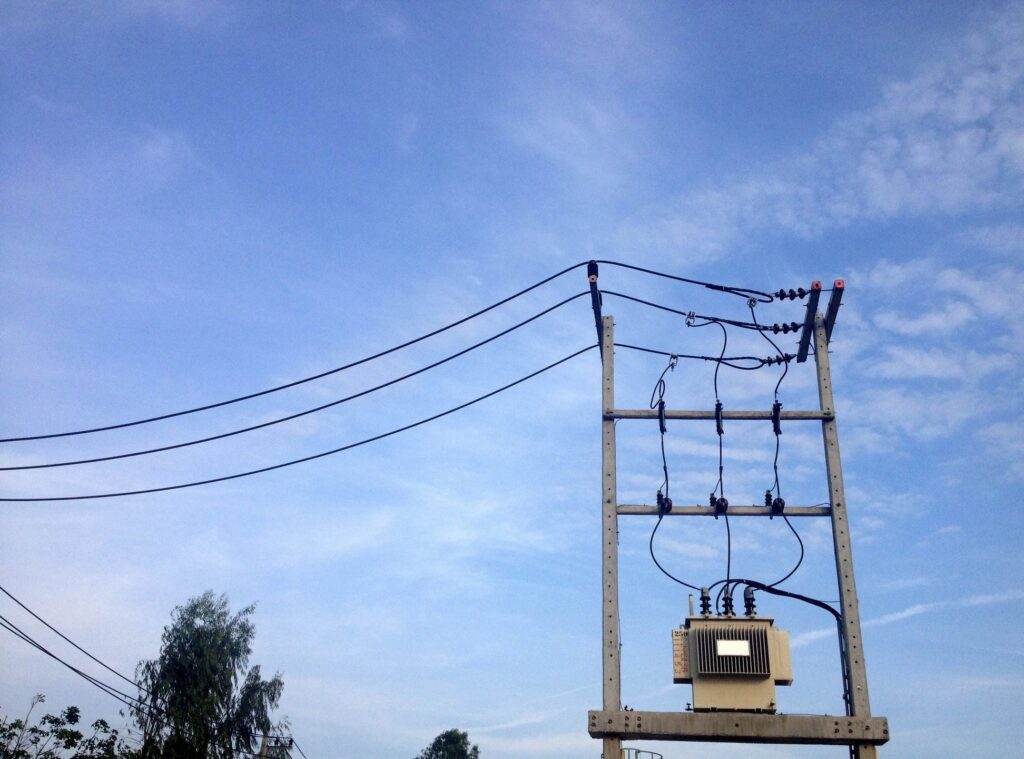

House Bill 244 is a follow-up to a bill lawmakers enacted last year that authorized EMCs to enter the broadband business for the first time. Under this year’s legislation, the state Public Service Commission (PSC) will decide how much EMCs can charge telecom providers for broadband attachments to their utility poles.

A dispute between the EMCs and providers over pole attachment fees has been a key obstacle in the way of delivering broadband to rural communities. It’s a standoff policy makers say rural Georgia can no longer afford.

“COVID has shown the vulnerability of these folks who have to stay home from school and the businesses that can’t expand,” said state Rep. Ron Stephens, R-Savannah, chief sponsor of House Bill 244. “If they don’t have broadband, they might as well not have power.”

Some progress is being made on the rural broadband front. Comcast announced a $9 million investment in June to expand its internet services to nearly 8,000 homes and businesses in Haralson and Carroll counties in West Georgia.

Carroll EMC launched broadband after a feasibility study showed that two-thirds of its members didn’t have it, said Tim Martin, CEO of Carroll EMC.

“We started looking for partners,” he said. “We found a local broadband provider, Global Telecom, that committed to us because they live here and know the need.”

Martin said the local schools are particularly anxious to get broadband service because of the pandemic.

“They couldn’t even do virtual school,” he said. “They had to send packets of work home.”

Martin said the project wouldn’t have been possible without a $12.5 million federal grant, and that’s been the rub.

Dennis Chastain, president and CEO of Georgia EMC, the trade association representing the local EMCs, said the sparse populations of rural communities in Georgia make broadband deployment into those areas difficult.

“Our density per mile is around 10 customers on average,” he said.

On top of that, many of the people who live in rural areas are poor, Chastain said.

“No matter how bad they might like to have [broadband], they can’t afford it,” he said.

Another barrier to rural broadband deployment is that the Georgia EMCs are charging telecom providers $20 per pole per year on average for broadband attachments, well above the average of about $7 per pole set by the Federal Communications Commission.

While the EMCs say they can’t afford to extend broadband into many rural communities even at the $20 rate, providers say such a high rate makes it hard for telecom companies to justify investing in broadband service to rural areas.

Michael Power, CEO of the Georgia Cable Association, said the list of states that have adopted the FCC rate for pole attachments includes regional neighbors Louisiana, North Carolina and Virginia.

“We believe if the PSC adopts a true cost-based formula, the EMCs will receive a pole rate that fairly compensates them,” he said. “We think this is the right approach.”

Power said the EMCs could lower the pole attachment rates to $7 per pole and make up the difference from what they’re charging now by adding only 50 cents to their average customer’s monthly bill.

But Chastain said it’s not that simple. He said the amount EMCs would have to raise customer bills would vary widely among the 41 individual companies, which face different economic circumstances.

For example, In the area served by Reidsville-based Canoochee EMC, the population density is only eight customers per mile, making extending broadband more expensive than in more densely populated communities.

Annual per-capita income in the area is only $19,000, said Lou Ann Phillips, CEO of Canoochee EMC.

“Our schools and medical services are suffering because we don’t have [broadband],” she said. “[But] our [feasibility] study says it’s going to cost $53 million. Where’s it going to come from?”

The EMCs and telecom companies will get a chance to argue their cases on pole attachment rates before the PSC in hearings set for next month.

“We’re going to bring a lot of facts and history to the table and evidence to show that a majority of states … did in fact adopt the FCC formula or something close to it,” Power said.

“We’re going to show what the cost is to put the pole in the ground and the cost to maintain the pole,” Chastain said. “All we want to do is recover the fair cost of [the providers] using our facilities.”

The PSC is scheduled to decide pole attachment rates in mid-December. The new rates then would take effect next July 1.